Cartier: Extravagant and Sharply Disciplined

I walked into the Cartier Jewelry Exhibit expecting sparkle, as one does, but the scale and intention behind each piece stops one cold. Beyond making jewelry; Cartier shaped culture with a designer’s eye for architecture, history, and form. The exhibit moves through eras, influences, and entire worlds of craft, and each room builds on the last. It feels both extravagant and sharply disciplined, which is exactly why I wanted to see it in person. The tiaras, the Art Deco geometry, the global references, and the sheer craftsmanship all reveal a story about design that stretches far beyond diamonds.

Three Tiaras, Three Worlds of Influence

The exhibit opens with three remarkable tiaras, and each one hits with real power. Tiaras once felt normal at a dinner party, yet today they read almost like props in a child’s dress-up game. These, however, feel royal and precious, and they pull you in fast. The first piece, a bandeau, uses openwork geometric design inspired by Islamic architecture, and the look feels modern for 1911. Cartier designers studied non-European forms, and that curiosity pushed them into new shapes and ideas. The next tiara, a special order from 1912, reflects this clear shift in taste and ambition.

The final piece returns to France and to the art and architecture of the 1700s—swags, ribbons, and wreaths—reimagined in platinum that behaves almost like embroidery. This lighter touch changed jewelry design around 1905, when they moved away from using silver towards platinum. The material change itself allowed for unique shapes and a more delicate aesthetic.

Egypt, Obsession, and Art Deco Alchemy

After the 1922 discovery of Pharaoh Tutankhamun’s tomb, Egyptomania swept through Europe with real force, and Cartier moved quickly. Their designers studied ancient Egyptian motifs through books and the antiquities on display at the nearby Louvre. That research shaped their Art Deco work, and the influence shows in every color combination, symbol, and piece of faience. The first piece, an onyx and diamond necklace, sets the mood with sharp contrast and clean geometry.

Next comes a mother-of-pearl, turquoise, emerald, pearl, diamond, enamel, gold, and platinum vanity case—try saying that list three times fast. The final pieces are scarab brooches made with blue-glazed faience, rubies, emeralds, citrines, onyx, diamonds, gold, and platinum. Each one creates a rich mix of materials and shows how Cartier turned ancient symbols into modern luxury.

Three Cultures, One Creative Thread

These three pieces reveal how Cartier absorbed global influences and turned them into something fresh. The bazuband for Sir Dhunjibhoy Bomanji reflects Cartier’s interest in Indian jewelry traditions, which favored bold silhouettes, arm adornment, and lavish gemstones. Cartier honored that history but reshaped it with crisp metalwork. The sautoir owned by Nancy Lancaster moves in a different direction and draws from the elegance of the early 20th century, when long strands of pearls and rubies framed the body with real drama. (You can also visit my post on her home, Cliveden House, which is a showpiece of its own.) Cartier used platinum to add structure without weight, and that choice gave the piece its iconic drape.

The wisteria brooches sold to Ernest Cassel return to nature for inspiration, and the cascading form mirrors the plant’s drooping blooms. Cartier loved botanical motifs, and these brooches show how they captured movement and delicacy with gemstones. Together, the three pieces reveal Cartier’s constant study of the world and its beauty.

Asia’s Influence

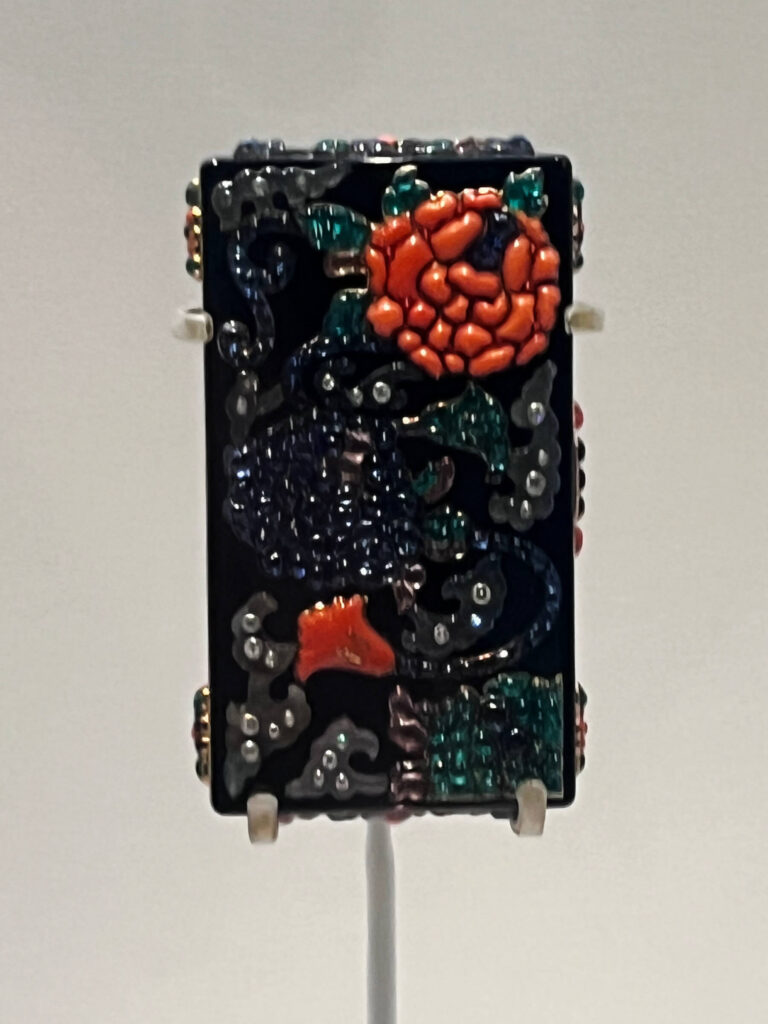

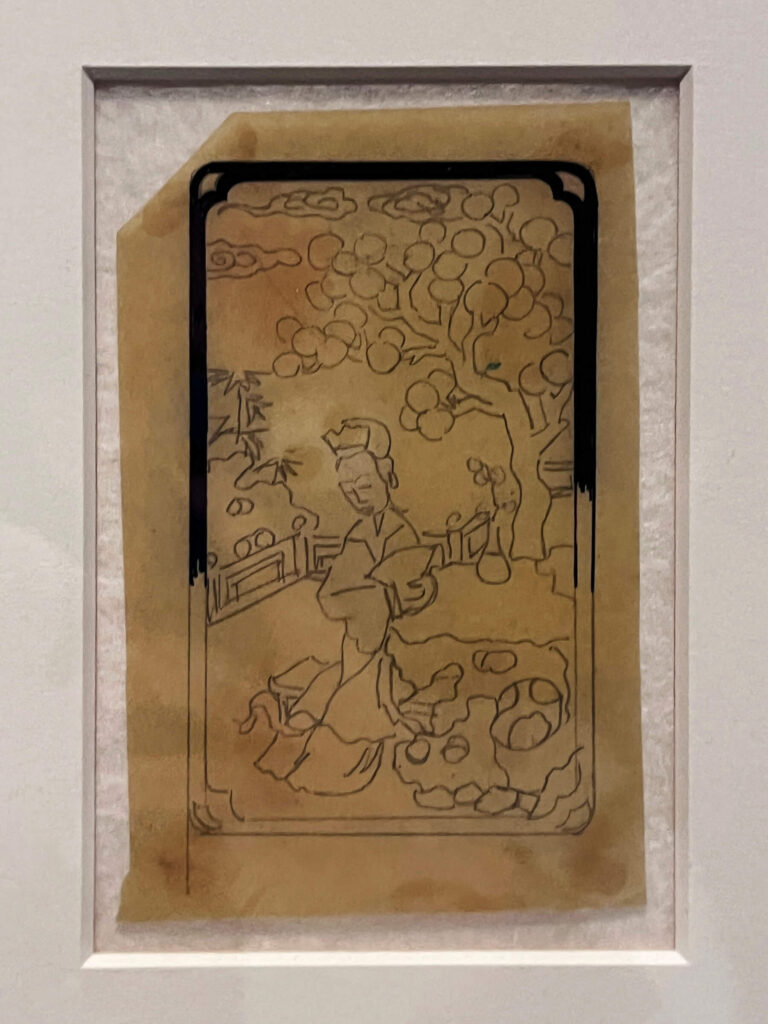

A 1945 Japanese mirror clock mixes coral, mother-of-pearl, diamonds, glass, enamel, lacquer, gold, platinum, and silver. Its form stays restrained because it follows Japanese craft with clean lines and precise patterning. Cartier valued Japanese design for its balance and clarity, and this clock proves it. The jade and coral pendants push the story forward and blend Art Deco geometry with softer Asian curves. Their jade centers ground each piece, and enamel and platinum add sharp detail. The suede clutch from 1927 layers jade, onyx, mother-of-pearl, coral, enamel, diamonds, silver, and gold. Its structure recalls the strong borders and tight grids found in traditional Chinese screens.

Cartier designers studied Chinese lacquerwork and ornament, and that influence shows in the tight borders and strong color contrasts. The necklace owned by Grace Curzon pushes the mix further with pearls, coral, onyx, emeralds, diamonds, platinum, and silk. Each material choice feels intentional and shows how Cartier balanced color, weight, and movement. The 1927 vanity case confirms the point with Chinese-inspired symmetry, a lacquer-like sheen, and crisp motifs. Cartier looked closely at Asia’s visual language—its materials, structure, and symbols—and used that research to shape work that feels modern and global.

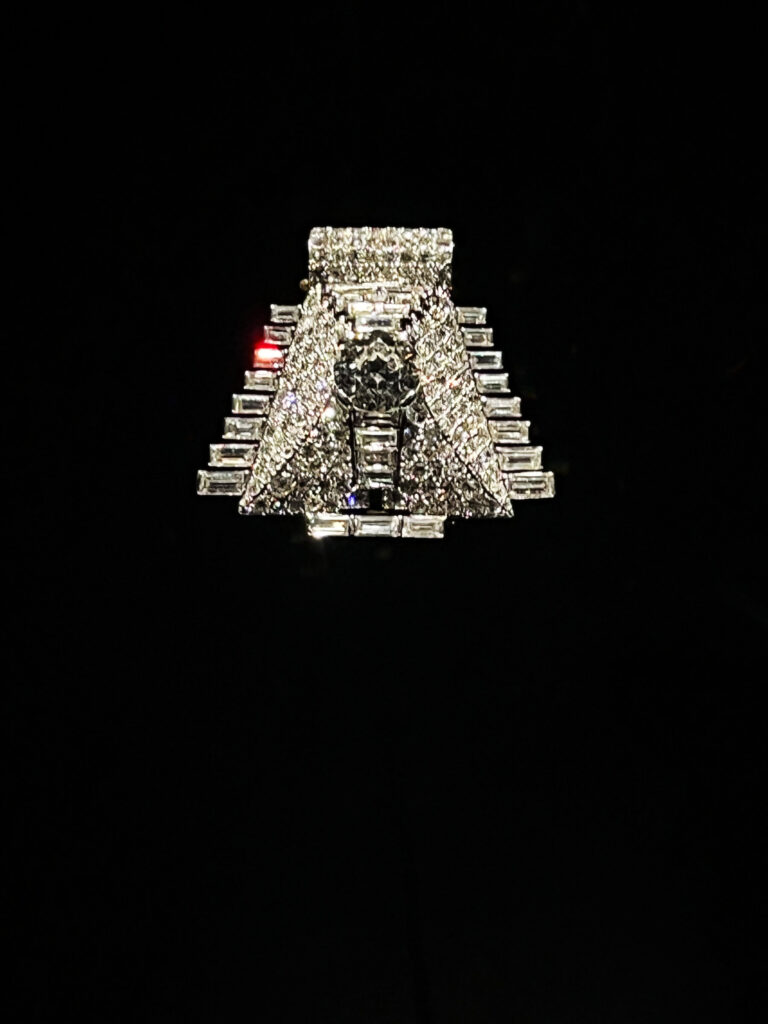

Cool Beauty: Hair, Feathers, and a Pyramid of Diamonds

This part of the exhibit focuses less on architectural influence and more on pure beauty, and the pieces still feel fresh. The 1924 New York head ornament sets the tone with a briolette diamond band and a dramatic feather that moves with every step. A curvy hair ornament from 1902 follows, once owned by Lila Vanderbilt Sloane, and its diamonds and platinum create a sculptural line across the head. The last piece, a pyramid clip from 1935, nods to the long aftershock of Tutankhamun’s discovery, and its sharp geometry still reads as modern. These three objects break from the usual tiara or necklace format and make a real case for the return of luxury hairpins and brooches.

Playfulness, and Stones With Attitude

These colorful pieces feel more casual at first glance, yet they stay fully decadent and create a playful shift in mood. The emerald and sapphire necklace from 1923 leads the group, and the fewer diamonds let the larger stones dominate. The color feels saturated, confident, and far less formal than Cartier’s earlier work. The next necklace moves in the opposite direction with an almost all-diamond design anchored by a 143-carat emerald. The final piece, a 1951 commission filled with rubies and diamonds, pushes color even further and shows how Cartier kept experimenting long after the Art Deco era ended.

Living My Dress-Up Dreams

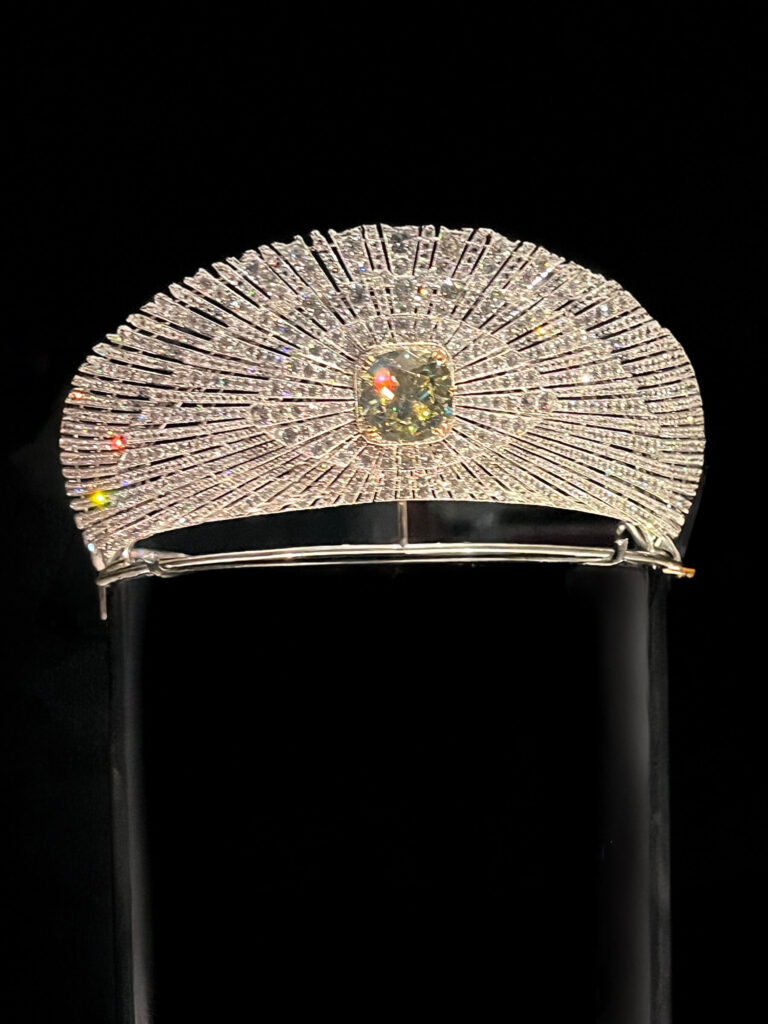

We circle back to tiaras—my dress-up dreams—and this group steals the show. My favorite piece, the aquamarine, diamond, and platinum tiara, comes from Cartier London during a moment of peak production. Cartier made an unusual number of tiaras in 1937. This one sold in April, only weeks before the coronation of King George VI in May. The central motif detaches and works as a brooch. A second row of aquamarines was added five months later, which gives the piece a stronger, more architectural line. Another standout is the citrine tiara, a stone that gained popularity in the 1930s and often went by “topaz.” The central clip in this piece was once recorded as a 62-carat topaz, also made in 1937 – another coronation-year commission.

A peridot necklace and bracelet set rounds out the palette with more than 325 carats supplied by the client. Cartier finished both pieces with crisp platinum detailing, which gives the bright green stones real presence. The three pieces together show how Cartier played with color, shape, and transformation during a moment when tiaras still carried status and imagination.

Timepieces

Tiaras and massive stones—emeralds, rubies, citrine, peridot—belong to another era, but timepieces still carry real power. A great watch remains the clearest signal of taste, wealth, and luxury. Cartier’s watchmaking imagination took off through its collaboration with Edmond Jaeger, whose ultra-thin movements freed the Maison to focus on shape and purity of line in each case. You see it in the radiating Roman numerals, the rail-track minute scale, and the distinctive setting details that define their early designs. These watches solved practical challenges, yet they also lived as jewelry, which makes the mix even better. Most of the pieces in this section come from the first two decades of the 1900s, some set with gems, others pared back with simple leather bands, all of them beautifully disciplined in form. The final three jump forward into the 1970s, and the double-strap wristwatch deserves its own comeback.

Regal Pieces

We swing back to tiaras—I promise I’m simply following the flow of the exhibit, which was carefully curated by Helen Molesworth, Senior Jewellery Curator at the V&A—and the final gallery holds the largest and most regal pieces of the entire show. The placement feels intentional, almost theatrical, as if Cartier saved the grand finale for those of us who live for this level of sparkle. These are the pieces that close the exhibit with real weight: scale, presence, and a kind of royal drama reserved for queens, weddings, and public life.

Cartier Jewelry Exhibit: Chasing Design

The Cartier Jewelry Exhibit reminded me why I chase design everywhere I travel. Cartier’s work may not link directly to my role as a Boston interior designer, yet the history, detail, and architectural influence behind each piece feed the same creative instinct. Design tourism keeps my eye sharp, and museum visits—large or small—give me a different kind of education. That perspective always finds its way back into my projects.