Historic English Estate Design

Meghan Markle spent the night here before marrying a prince, which feels entirely appropriate. Cliveden House has long attracted the type who favor silk robes, staff entrances, and an audience. Built high above the Thames, it’s grand, deliberate, and unapologetically architectural—a masterclass in historic English estate design. Every arch, terrace, and column reminds you that beauty here was planned, not improvised.

Though its grandeur feels unmistakably English, Cliveden’s story is part American. William Waldorf Astor purchased the estate in 1893, once the richest man in America, and he poured his fortune into restoring and expanding it. His son and daughter-in-law Nancy Astor transformed the house into one of the most famous salons. In the early twentieth century, they hosted writers, politicians, and royals. Last but not least, Nancy was also the first woman to take a seat in the British Parliament.

I recently met Emily Astor, granddaughter of Nancy Astor, who grew up at Cliveden. Along with Jane Churchill—a relative by marriage, elebrated designer, once co-owner of Colefax & Fowler—they hosted a dinner at the estate and gifted me their book, Entertaining Lives: Recipes from the Houses of Nancy Astor and Nancy Lancaster. The collection weaves together family recipes and stories that link Cliveden’s English grandeur with its American roots in Virginia. I’ll share more on that cookbook soon—but first, a closer look at the estate itself.

Unapologetically Grand

A true grand dame among English houses. Cliveden has hosted its share of titled residents—two dukes, an earl, a prince, and later, a viscount. Built in 1851 and now Grade I listed, the name Cliveden translates to “valley between the cliffs,” a nod to the wooded valley that cuts through its 375-acre estate of gardens, lawns, and ancient woodland.

At its approach sits the Fountain of Love—marble, mythic, and entirely unapologetic. Lord Astor commissioned it in 1897, likely because understatement was never his problem. Three carved figures lean from a giant scallop shell, surrounded by a basin wide enough to drown your ego. The water soundtracks your arrival, echoing off stone like applause.

Classical Symmetry

Cliveden began with a house built in 1666; fires in 1795 and 1824 forced two rebuilds. The current house, completed in 1851, is the most commanding version yet. A three-storey mansion set on a terrace framed by woodland and formal gardens.

The front gardens are geometry at work. Stone balustrades, iron gates, and clipped hedges form a lesson in control. Even the lanterns look regimented. Charles Barry, the architect who rebuilt the house, extended symmetry from facade to grounds so every step aligns with an axis. Stone sarcophagi line the forecourt, flanking the approach. Part of Lord Astor’s 19th-century collection of classical sculpture, they were placed deliberately to heighten the estate’s Italianate grandeur. My favorite detail: hedges pruned to frame each sculpture with precision.

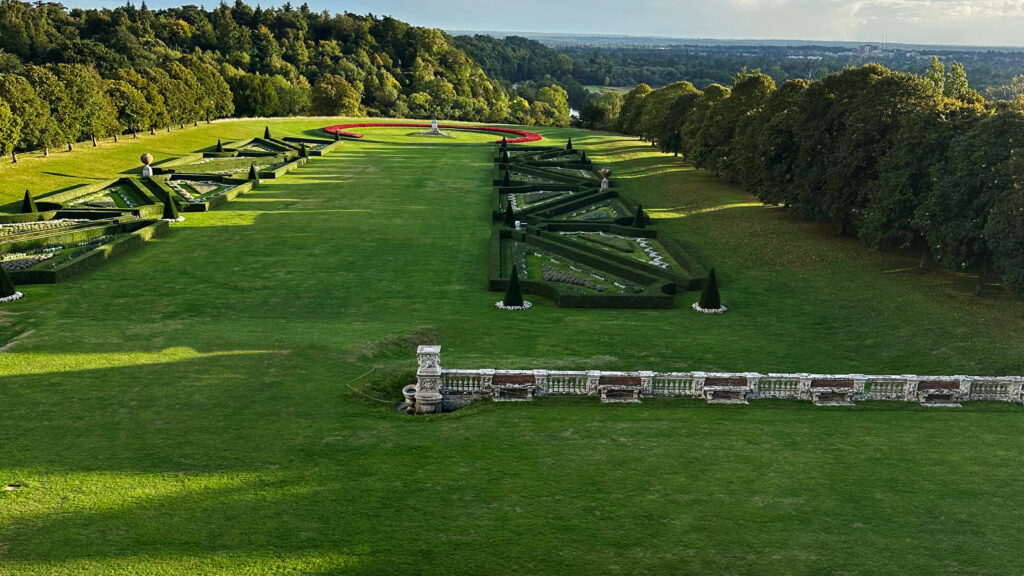

Precise Green Geometry

The terrace at the back sits on the footprint of earlier homes lost in the fire. Anchored by aged brick and stone arcades, Barry designed it to mirror the mansion’s rhythm. Each arch balancing a window above. Below, the parterre unfolds in precise green geometry. Hedges, benches, and urns align like notes in a score, and a bronze figure holds court at the center. Every angle is a composition. Pro tip: view it from the upper balcony—it’s the best seat in the house.

Devotion & Design

Head to the western side of the Parterre for a surprise: the modest domed building overlooking the river hides a richly detailed chapel, once known as the Octagon Temple. Built in 1735 for Lord Orkney by architect Giacomo Leoni, it originally served as a tea pavilion where guests could stroll the cliff-top paths before taking tea in the “Prospect Room.”

When William Waldorf Astor purchased the estate in 1897, he transformed the tea-room into a private chapel, adding major structural changes that created a soaring double-height space. At Cliveden, devotion and design seem to share the same blueprint.

Cottages and Outbuildings

Several cottages dot the estate, each designed with too much care to feel like an afterthought. Builders used brick, timber, and leaded glass—never halfway measures. George Devey designed or refined most of them in the nineteenth century, proving that even staff quarters needed to look good from the main house. Down by the river, Spring Cottage is a guest retreat with its fair share of gossip. Today it’s polished and private, a small hideaway that redefines what counts as an outbuilding.

I’m drawn to the picturesque detailing—clustered chimneys, vertical accents, and asymmetrical rooflines. With pampas grass and deep greens along the Thames, it all feels settled, timeless.

The Boathouse: Timber, Brick, and Local Tile

The boathouse was one of several structures added or remodeled in the late 1850s under Devey, who designed it in a rustic mix of timber, brick, and local tile. Now a Grade II–listed building, it remains part of Cliveden’s river heritage. A recent restoration even revived Liddesdale, a historic canoe once used on this stretch of the Thames.

My takeaways: the red-and-black checkered tiles feel more chic than board game, and the webbed seats in the boats caught my eye—not historic, but they reminded me of the woven craftsmanship of Risom chairs, a favorite mid-century piece from the 1940s.

Rear Facade & Italianate Details

A view from the west catches the house through a break in the trees, revealing the open-air viewing gallery and the sturdy stone flank of the structure itself. The balcony above—where I was invited for cocktails—feels even grander when seen from below. We were lucky to catch the estate on a bright afternoon, the stone glowing gold against the sky instead of fading into London’s familiar grey.

Norah Lindsay’s Roses

Beyond the main lawns, the rose garden introduces a rare dose of sentimentality. Reimagined in the 1930s by Norah Lindsay, one of Britain’s most influential garden designers, it’s a study in controlled softness: trellised entries, stone urns, and ombré blooms fading from blush to crimson. Romance, yes—but always under control.

Precisely Pruned

Leading from the rose garden back toward the main house, the path is lined with my favorite element—precisely pruned hedges. Framing an arched opening with a view of the clock tower, it was added in 1861. Today, it still serves its original purpose as the estate’s water tower.

From here, more views open to the front gardens and the main approach. I’m hardly a practiced gardener, but even I can appreciate the late-season color. The green heads of wild leeks (resembling alliums), pops of pink from showy stonecrop, and layers of Russian sage. Purple deepens through New England asters and grape-leaf anemone. White and magenta cape marguerite and the soft lavender hue of aromatic asters tying it all together—whites and greens paired with purples and magentas in perfect balance.

All late bloomers, these plants thrive in the mild warmth of an English autumn. They work because the soil stays moist, frost comes late, and the light softens rather than fades. In Boston, you can get a similar look from late August through early October—Russian sage, asters, sedum, and anemone are all hardy enough.

Classic, Symmetrical & Worth the Wait

Back at the entrance to the estate, there’s a better view of the clock tower—a spiral stair, half-sheltered, curling upward in measured drama. Just as we reached the front entry, a red double-decker bus rolled in for a wedding, because the British really can’t resist their own iconography. When it finally pulled away, the view cleared for a proper photo of the entry—classic, symmetrical, and worth the wait.

Any Link, However Small, Feels Special

Just a stunning property. As a New Englander, I’m spoiled by history—Boston, Massachusetts, and all of New England are full of it. Newport and its storied mansions are only an hour away, but I’d never really visited a true English estate until now. I loved noticing the differences between historic estates in the U.S. and England—and the connections too, especially since this one belonged to the Astors. My own grandfather worked at the Waldorf Astoria in New York, and any link, however small, feels special.

As a student of architecture and a designer, I found the details mesmerizing—the craftsmanship, the layers, the proportions. Sitting down with Emily Astor and Jane Churchill, both English with American roots, made it even better. Each grew up visiting Cliveden when it was still a private home.

Beyond sharing photos, all I can say is this: visit if you can. And if not, buy the cookbook— Entertaining Lives—it’s a charming look at life inside this remarkable house. Read more about the cookbook here, and see the interiors of Cliveden here—equally grand, equally unforgettable.